ABSTRACT

Muslims observe fasting amongst many other rituals during the month of Ramadan. The Quran states the purpose of fasting is to attain taqwa- piety. Other rituals such as prayers and charity also facilitate attaining piety. While piety is a religious concept, it is underpinned by many neurobiological processes. Modern research provides increased clarity on the neurobiological effect of rituals and how they lead to piety. This paper addresses the interface between the religious and biological basis of piety, especially relative to fasting.

Keywords: Fasting, Ramadan, Neurotheology, Piety, Taqwa, Religiosity, Spirituality.

Introduction

Extensive studies have shown the positive impact of fasting on health. Some of the positive effects of fasting include the positive change of blood sugar and lipids, body fat, weight loss, cognitive function, improved immunity, and many others. 1 2 Fasting is also associated with improvement in mood, alertness, and a sense of tranquility.3While the health benefits of fasting are believed by Muslims and taken for granted, the Qur’an and Sunnah highlight a different benefit of fasting, which is the effect on the state of التقوى” taqwa” “piety” and, ultimately, its reward in the hereafter. This paper delves into the concept of taqwa and how the observance of Ramadan impacts it from a biological perspective.

Part I

Taqwa

Significance of Taqwa

The word taqwa and its derivatives appear 258 times” in the Qur’an, of which 182 times was in the verb form and 76 times as a noun, which makes taqwa a very prominent concept in the Qur’an.

The purpose of fasting is specified in the following verse:

“O ye who believe! prescribed unto you is fasting even as it was prescribed unto those before you, that ye may have taqwa.” 4

So it is specifically stated fasting aims to help people to attain taqwa.

The Quran also states that the worshipping Allah solely is the purpose of the creation:

“And have not created the Jinn and mankind but that they should worship Me.” 5

The purpose is of worship is stated in the following verse:

“O Mankind worship your Lord who has created you and those before you so that you may attain taqwa.” 6

As such, all ritual and worshiping activities aim to facilitate attaining taqwa. Hence, it is of paramount importance to understand the concept of taqwa, so the purpose of worship is achieved.

Definition

Taqwa comes from the root verb “waqaya” وقي , which means “to protect or prevent harm.” In the technical sense, it simply means to take measures that shield a person from Allah’s dissatisfaction by following His commands and avoiding His prohibitions. However, the companions of the prophet gave a practical example of the practice of taqwa, peace be upon him (PBUH). Omar bin Khattab taught us the meaning of taqwa by asking Ubay ibn Kaab about it. Ubay gave a practical example asking: “Have you ever walked on a path that has thorns on it?” Umar said, “Yes.” Ubay asked, “What did you do then?” to which Umar replied, “I rolled up my sleeves and struggled [seeking what is safe].” Ubay said, “That is taqwa, to protect oneself from sin through life’s dangerous journey so that one can complete the journey unscathed by sin”.7 A deeper analysis of this example reveals the core element of taqwa. It is natural and instinctual for people to maintain their wellbeing by seeking what is safe and avoiding harmful harm. Any experience people go through would normally generate reactions to serve this purpose. That includes the response to harm or threat via the fight-or-flight response produced by a series of phycological processes involving the nervous system and certain hormones. Similarly, taqwa is the spontaneous natural inclination to do what is good and avoid what is evil.

Therefore, it is important to delineate two different aspects of taqwa. The main one is what we just explained above, which is the true taqwa. The second one is the exercise of forcing oneself to discipline and the practice of taqwa. There is a very clear distinction between the two. The first is the natural trait “sajiyah” ةّسجی while the second is an exercise to practice, that is ّف “takalluf“ تكل and “mujahadah” مجاھدة . This concept is highlighted in the advice of the prophet (PBUH): “[gaining] knowledge is by learning and [becoming] patient is be exercising patience” 8 and “Whoever exercises patience, Allah will make him patient.” 9

Again, the above examples given by the prophet (PBUH) emphasize the acquiring any attribute can become a sajiyah through proper exercise and mujahadah. In the case of taqwa, the same word happened to refer to both aspects, the train and process of exercise, hence the vague understanding of the concept of taqwa.

To recapitulate, taqwa can be defined as the trait of spontaneous and natural affinity or inclination to do what is good and avoid evil and is achieved by exercising taqwa!

Taqwa Index (IT)

To translate the concept of taqwa into a practical one, it may be beneficial to quantify taqwa and attach a numeric figure to it so a person may track it over time, especially pre-and-post Ramadan since the main goal of worship is to attain taqwa, as explained earlier. Of course, this is not a scientifically validated index but an attempt to benchmark the effort and progress made by a person in the journey of reaching Allah. This is a fulfillment of the advice of Omar:

“Audit yourself before you are audited and weigh yourself before you get weighed.” 10

It is clear from the concept of taqwa that it involves two different arms, one of doing what is good and the other is avoiding what is evil. Each arm needs to be graded. For the first one, we can have a scale from 0 to 10, where 10 is the most pleasurable activity a person encounters, and 1 is the least. Pick the most pleasurable activity in life (such as a hobby or anything that give joy and pleasure) and give it a score of 10. Then score the comfort and pleasure achieved in prayers “salah” relative to that. Prayers were selected due to their known status in Islam and as ritual described by the prophet (PBUH) as his ultimate comfort:

“My comfort [eye coolness] has been put in salah.” 11

A person may choose to grade different worship activities and rituals and determine where they fit on a scale.

As for the arm of avoiding evil, we can similarly have a scale from 0 to 10, where 10 is the most disliked thing to a person, and 1 is the least. Consider being put on fire as the score 10 on the described scale. Pick any shortcoming you have (such as losing control over your gaze) and score it 1-10 relative to that. The fire example was chosen as the prophet used it to describe the extent to which a believer should hate reverting to the state of disbelief. He said:

“Three [qualities] if present in any person, they experience the sweetness of faith: Whoever Allah and His Messenger are dearer to than anything else; Who loves a person and he loves him only for Allah’s Sake and who hates to revert to disbelief as he hates to be thrown into the Fire.” 12

Now you can take the two values obtained in the above exercises and divided them by 2, the product of which is considered the TI!

This To do repeatedly but particularly before and the month over Ramadan to assess the impact of rituals practiced in that month on piety.

Needless to say, this exercise is claimed not to be part of Sunnah, nor is it required as a ritual, or it would fall into innovation. However, it should be perceived as a tool for self-assessment amongst many others.

Part II

Fasting and Behavior

Human Behavior

It is often invoked that humans are species of habits. Scientifically, that’s very true. Many human actions are based on habits. Humans maintain some habits without much contemplation behind them. Some habits are irresistible and hard to change despite the massive effort and time consumed. Habits are a substantial component of our daily lives.

But how are habits deeply rooted in our biology?

Let’s take one example, then first, and then try to analyze. It’s deeply rooted in our culture to have lunch at noontime. You are very preoccupied working in your office and have lost track of time. Suddenly you look at the wall clock and realize it is 12 o’clock. You feel you are hungry, and you have to get up and eat. You get up to get a meal but also remember to browse your phone for messages while eating. You go on YouTube and watch some clips. Of course, you have to get your favorite dessert and a beverage afterward. And more. All these actions are tied together. It is part of your “daily routine.” You have become so habituated. These habits have become part of you, and they are tough to break. The following section will explain how our body and mind “learned” this routine.

Concept of “conditioned response.”

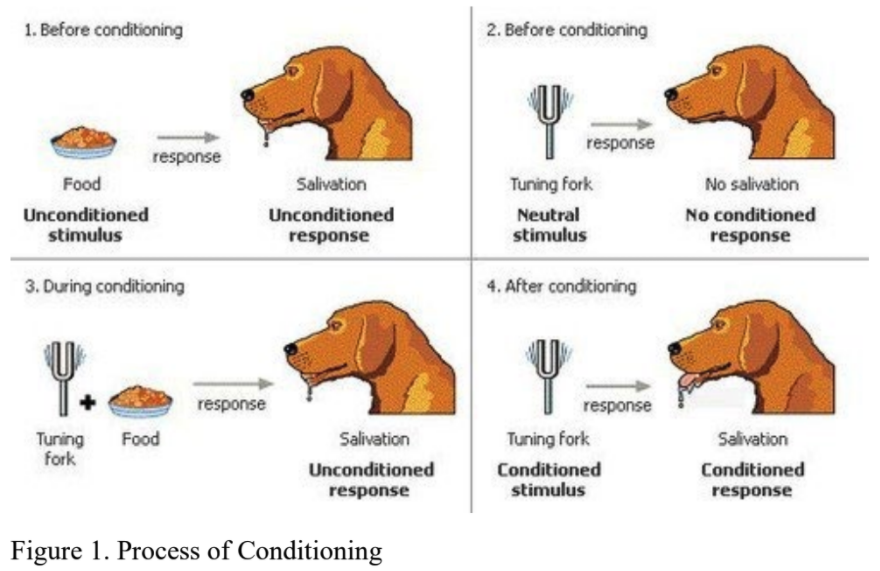

Conditioned responses underpin many of our daily life behaviors. Understanding this concept facilitates understanding much of how and why we do what we do. The concept of a conditioned response has its origins in classical conditioning and was discovered by the Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov in a series of simple and brilliants experiments. Pavlov studied the salivation responses of dogs to different stimuli. A stimulus is an event or anything that would call a reaction, which we call a response. Pavlov noticed that while dogs would naturally salivate when food was in their mouths, they salivated at the sight of food. Some dogs would even salivate when they heard the footsteps of the person who gave them food coming down the hall.

Pavlov conducted experiments to determine if his observation would be replicated by evoking a response (salivation) to other neutral stimuli. A neutral stimulus would not evoke a response normally. When the food is introduced to the dog, a salivation response is observed. Now the food is introduced along with a sound produced by a bell or tuning fork. This is done several times, so the stimulus is “learned” by the dog. Now the food is withdrawn. When the sound stimulus is produced alone without the food, the dog will salivate. The dog has been conditioned to what was originally a neutral stimulus, the tuning fork sound in this case. This process of “conditioning” is easily achieved by the repeated “pairings” of the neutral stimulus (sounds) and the actual original natural stimulus (food). The same salivation response may develop to other neural stimuli, such as turning the light on by paring it repeatedly to the food. Any neutral stimulus as such may be turned into a “conditioned” response.

(image credit: medium.com)

While salivation in response to the food is an unconditioned response because it happens automatically, salivation in response to the neutral stimulus is a conditioned response because it is a learned reflex.

If the experiment is repeated several times and the sound stimulus is introduced without the food, the salivation responses would gradually diminish and eventually vanish completely. At that point, the dog is “unconditioned” and would “unlearn’ the conditioned stimulus, which would become neutral again.

The stronger the association between the original natural stimulus and the neutral stimulus is, the stronger and the longer the conditioning process be. This would be achieved by intermittently repeating the “painting” process. Inversely, the weaker the association between the conditioned stimulus and the original stimulus, the weaker and shorter the response would be. This would be achieved by not introducing the original stimulus anymore. This conclusion is key in understanding the effect of fasting on behavior, as explained in a little.

Examples of conditioned responses

Now that the conditioned response concept is clear, you will be able to identify a countless number of “learned behavior” examples, starting with tricks trainers use in animal shows, why you get hungry at a certain time, and finally, drug addiction. Many of the fears and phobias “learned” or acquired over time may be explained by this Pavlovian process. More practical examples will be discussed later as the impact of fasting on habits is explained.

Reward and pleasure

Pavlov’s observations and experiments were able to explain many of our learned behavior and habit formations.

Modern science is now able to explain these observations more profoundly to the molecular levels.

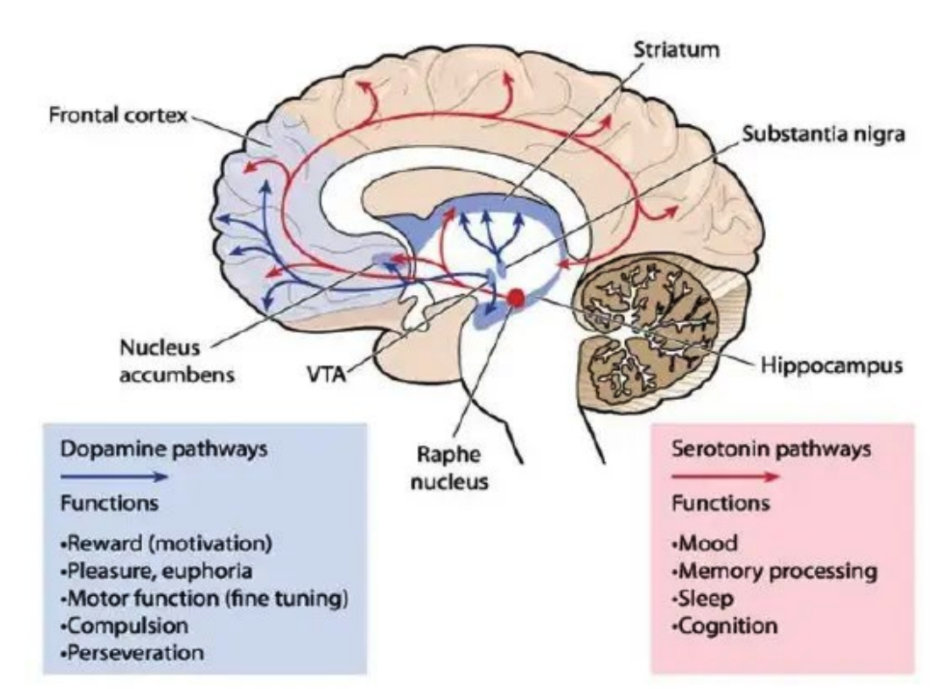

Emerging evidence from animal and human research suggest that this type of processing is mediated in part by an area in the brain called the nucleus accumbens and a closely associated network of brain structures. Additionally, this structure is critical for acquiring and expressing most Pavlovian stimulus-reward relationships, and cues that predict rewards produce robust neural activity changes in the nucleus accumbens. While processing within the nucleus accumbens may enable or promote Pavlovian reward learning in natural situations, it has also been implicated in aspects of human drug addiction, including the ability of drug-paired cues to control behavior. 13 The main neurotransmitter that communicates between this area and other areas of the brain is called dopamine.14

Dopamine is critical in all sorts of brain functions, including thinking, moving, sleeping, mood, attention, and motivation. It plays a major role in the “pleasure” experience. Not only does dopamine makes you feel enjoyment and pleasure, thereby motivating you to seek out certain behaviors, such as food, sex, and drugs, but dopamine is also critical in causing seeking behavior. Dopamine causes you to want, desire, seek out and search. It increases your general level of arousal and your goal-directed behavior. 15 Specifically, dopamine created in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the brain is associated with rewards. Dopamine is released from the VTA into the rest of the brain when a person does something and receives, or even expects, a “reward” or pleasure. This spike of dopamine then motivates the person to continue performing this behavior that brought them the reward. Dopamine helps drive humans towards necessary actions, like drinking water and eating food, but can also bring people to act on less healthy behaviors, like binge eating or drug use.

Dopamine, in summary, is the major player in the brain experience of “pleasure” and seeking “reward.”

Unlearning Conditioned Responses

It is sometimes difficult to determine if a response is conditioned or unconditioned. In general, n unconditioned response happens automatically while a conditioned response is learned and only acquired if the individual has an association between an unconditioned and conditioned stimulus.

Because a conditioned response must be learned, it can also be unlearned. That is achieved by gradually diminishing and eventual disappearance of the conditioned response, which is called extinction. 16 Unlearning is one of the main mechanisms in how fasting changes behavior, as we will soon discuss.

Physiologically, the combination of dopamine release in the brain plus a conditioned response associated with pleasure enhances what we call a dopamine loop. When you, dopamine is released, which makes you feel pleasure, and that makes you want to wat more, but as dopamine is depleted, you feel less pleasure, but you tend to eat more to achieve that pleasure. That is the vicious cycle that leads to addiction. This dopamine-associated response is hard to stop. The best way to avoid dopamine “bankruptcy” is to break the dopamine-seeking-reward loop once it has started. 17 Fasting does that at different levels.

Fasting Impact on Behavior

It is now clear how fasting would impact behavior. It is evident that many of our behaviors in daily lives are nothing but learned behaviors. Fasting requires us to “unlearn” many of the behaviors and “un-condition” our responses.

Fasting requires abstaining from oral intake and sexual relations from sunrise to sundown. Meals are not scheduled at unusual times, before sunrise and right after sundown. This process dissociated the time conditioning and made a person subject to a different schedule. The time pattern of Ramadan follows the lunar calendar, which makes it vary from year to year. And the days of Ramadan follow the solar system, which makes it vary from date today. There is not a fixed schedule for Ramadan. You are subject to an external schedule and not your own conditioned responses. By the end of Ramadan, the sense of hunger is true and is not associated with the conditioned stimulus of time or other memories. Physiologically, the dopamine loop is weakened, and the dopamine is kept in check. Similarly, the opportunity time for intimacy is significantly restricted, diminishing the conditioned response and regulating dopamine. The same concept applies to sleep as the regular sleep pattern is disrupted, and the nature of Ramadan’s schedule dictates a new sleep schedule.

On the other hand, Ramadan brings to you homework that goes beyond fasting. It busies you with rituals such as Quran recitation and praying Taraweeh. These activities would diminish the chance for the learned habits, including “seeking” and addictive behaviors. It would also stimulate the brain areas responsible for well-being and mood stability mediated by the “serotonin circuit” while turning off the dopamine circuit.18 This is the same mechanism that explains the popular “dopamine fasting” concept.19

www.AusMed.com

Research has actually shown the plasma levels of serotonin, and other healthy chemicals to the brain, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor and nerve growth factor, were significantly increased during the fasting month of Ramadan.20

Conclusion

We demonstrated that many human behaviors are “learned behaviors” underpinned by brain reward response and mediated by dopamine. Fasting leads to “unlearning” and un-conditioning

many of our behaviors and diminish the dopamine response. Other rituals, including Quran recitations and prayers, would enhance serotonin response, which is responsible for well-being and stability.

Taqwa, the biggest fruit of Ramadan, is restoring a healthy chemical balance of our being. It is the liberation selves from the slavery of dopamine responses and conditioned behavior and allowing our actions to be based on our intelligent decision and not reflexes. Taqwa is simply a reboot of the brain to its most functional and healthy state.

References:

- Nachvak SM et al., “Effects of Ramadan on food intake, glucose homeostasis, lipid profiles, and body composition,” Eur J Clin Nutr (2019): 73(4):594-600.

- Mindikoglu AL et al., “Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for 30 consecutive days is associated with anticancer proteomic signature and upregulates key regulatory proteins of glucose and lipid metabolism, circadian clock, DNA repair, cytoskeleton remodeling, immune system and cognitive function in healthy subjects”, J Proteomics (April 2020): 5;217:103645.

- Fond G et al., “Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature”, Psychiatry Res (2013): 30;209(3):253-8.

- The Noble Quran, Al-Baqarah, 2:183

- The Noble Quran, Adh-Dhariyat, 26:56

- The Noble Quran, Al-Baqarah, 2:21

- Muhammad Saed Abdul-Rahman, The Meaning and Explanation of the Glorious Quran, (MSA Publication Limited, 2009), 63.

- Sunan an-Nasa'i : 2588, accessed May 25, 2019, https://sunnah.com/urn/1125970

- Tabarani: 3/118, 2588, accessed May 25, 2019, https://dorar.net.

- Ahmad: Azzuhd, 2/68

- Sunan an-Nasa'i : 3940, accessed March 3, 2020, https://sunnah.com/nasai/36/2

- Sahih Alnukhari: 6941, accessed March 3, 2020, https://sunnah.com/bukhari/89/2

- Day J, Carelli R, “The Nucleus Accumbens and Pavlovian Reward Learning” Neuroscientist (2007): 13(2): 148–159.

- Dravas M, “Dopamine dependency for acquisition and performance of Pavlovian conditioned response,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (Feb 2014): 18; 111(7): 2764–2769.

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-wise/201802/the-dopamine-seeking-reward-loop

- https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-conditioned-response-4590081

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-wise/201802/the-dopamine-seeking-reward-loop

- Hamid B, “Chemistry of Happiness.” Jurnal Qalbu (Sept 2017): 40-62

- Bowles N, “How to Feel Nothing Now, to Feel More Later- A day of dopamine fasting in San Francisco,” The New York Times (Nov. 7, 2019)

- Bastani A et al., The Effects of Fasting During Ramadan on the Concentration of Serotonin, Dopamine, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Nerve Growth Factor. Neurol Int. 2017 Jun 23; 9(2): 7043.